The Quincy House

The Quincy Agent’s House is the last standing mining company agent’s house among the many mines that once exploited the area for copper. After nearly 50 years of ownership by the Anderson family, David Bossert and Zachary Nick purchased the house in May 2021 with a long-term vision to restore, rehabilitate and revitalize the house back to its Victorian era splendor. The house is listed on the Michigan State Register of Historic Sites and lies within the Keweenaw National Historical Park. Copper Country Preservation, Inc., http://coppercountrypreservation.org/, accepts donations earmarked for the Quincy Agent’s House which have been used as matching funds for a 2016 Home Inspection, a Report on the Property’s History and Current Condition by Sarah Fayen Scarlett, PhD Assistant Professor of History, Michigan Technological University and consultation by Gianfranco Archimedes, Director, Historic Preservation for Paterson, NJ.

The 3.5 acre property includes its original buildings, a Victorian house, two-story barn with horse stalls, and two-car stucco garage. Many historic features are in surprisingly good condition. A significant large outcropping of rock with glacial tracks shows the geological heritage of the unique Keweenaw Peninsula formation. In springtime, the hillside blooms with lupines, poppies, phlox and lilacs against a backdrop of lawn, woods at a higher elevation. Amid old gardens and ancient oaks, a Victorian greenhouse foundation exists. The setting is beautiful in all seasons, perched on Quincy Hill overlooking the Keweenaw Waterway/Portage Lake and across to Houghton.

The 3.5 acre property includes its original buildings, a Victorian house, two-story barn with horse stalls, and two-car stucco garage. Many historic features are in surprisingly good condition. A significant large outcropping of rock with glacial tracks shows the geological heritage of the unique Keweenaw Peninsula formation. In springtime, the hillside blooms with lupines, poppies, phlox and lilacs against a backdrop of lawn, woods at a higher elevation. Amid old gardens and ancient oaks, a Victorian greenhouse foundation exists. The setting is beautiful in all seasons, perched on Quincy Hill overlooking the Keweenaw Waterway/Portage Lake and across to Houghton.

The architecture is Victorian Italianate. “The Quincy Agent’s House façade is dominated by a three-story square tower very much in the Italianate style, but its centered

placement is less typical. Italianate architecture more often embraced the visual variety of asymmetry. Approximately 15 percent of Italianate residences include the iconic square tower” (Scarlett, 2017) .

A porch spans the front of the house facing the waterway. An enclosed side porch and widow’s watch offers additional views of the valley.The 19-room 10,000 sq. ft. interior (not including attic and dungeon) has high ceilings, original white pine wood trim, wainscoting and plank floors. Double entry doors on the first floor lead to a central foyer with staircase, pocket doors to a parlor and music room with fireplaces, a library, an office/room with dressing room and bath with original claw-foot tub, marble sink and faucets, dining room, butler’s pantry, large kitchen “updated” in 1920s or 30s, double pantry/larders, summer kitchen and storage room at rear, trompe l’oeil painting in side entry hall, dumb waiter, servant’s staircase to 2nd, 3rd floors and sub-ground floor. The second floor features six bedrooms each with original marble sinks, 5 with original walk-in closets, a sitting room under widow’s watch, one bath and kitchen, two-room maids’ quarters with original claw-foot tub. The dungeon, a labyrinth of connecting rooms from a passage with a mysterious door, was perhaps used as a jail or asylum, as well as cold storage.

A porch spans the front of the house facing the waterway. An enclosed side porch and widow’s watch offers additional views of the valley.The 19-room 10,000 sq. ft. interior (not including attic and dungeon) has high ceilings, original white pine wood trim, wainscoting and plank floors. Double entry doors on the first floor lead to a central foyer with staircase, pocket doors to a parlor and music room with fireplaces, a library, an office/room with dressing room and bath with original claw-foot tub, marble sink and faucets, dining room, butler’s pantry, large kitchen “updated” in 1920s or 30s, double pantry/larders, summer kitchen and storage room at rear, trompe l’oeil painting in side entry hall, dumb waiter, servant’s staircase to 2nd, 3rd floors and sub-ground floor. The second floor features six bedrooms each with original marble sinks, 5 with original walk-in closets, a sitting room under widow’s watch, one bath and kitchen, two-room maids’ quarters with original claw-foot tub. The dungeon, a labyrinth of connecting rooms from a passage with a mysterious door, was perhaps used as a jail or asylum, as well as cold storage.

The laundry room showcases original Victorian double soapstone and iron sinks. A back staircase from the dungeon leads to the side yard and summer kitchen. The attic was recently insulated and mostly finished with local cedar paneling, yet the steep roof line leaves ample room as this space was likely used as a meeting hall and for dances during the Copper Boom. An original paint and shuttered widow’s walk or watch is up several stairs from the attic offers a magnificent view from three sides. The attic above the attic is a perfect hiding place. This house was once heated by steam via underground tunnels from the Quincy Mine hoist. The original infrastructure and unusual radiators still exist, though the house is heated by two energy efficient boilers. The electrical is updated; the plumbing is an ongoing project but the house is comfortable and livable with two hot water heaters. The wallpaper was updated in some bedrooms in keeping with the period although the interior cosmetic appearance needs work where old wallpaper remains.

The laundry room showcases original Victorian double soapstone and iron sinks. A back staircase from the dungeon leads to the side yard and summer kitchen. The attic was recently insulated and mostly finished with local cedar paneling, yet the steep roof line leaves ample room as this space was likely used as a meeting hall and for dances during the Copper Boom. An original paint and shuttered widow’s walk or watch is up several stairs from the attic offers a magnificent view from three sides. The attic above the attic is a perfect hiding place. This house was once heated by steam via underground tunnels from the Quincy Mine hoist. The original infrastructure and unusual radiators still exist, though the house is heated by two energy efficient boilers. The electrical is updated; the plumbing is an ongoing project but the house is comfortable and livable with two hot water heaters. The wallpaper was updated in some bedrooms in keeping with the period although the interior cosmetic appearance needs work where old wallpaper remains.

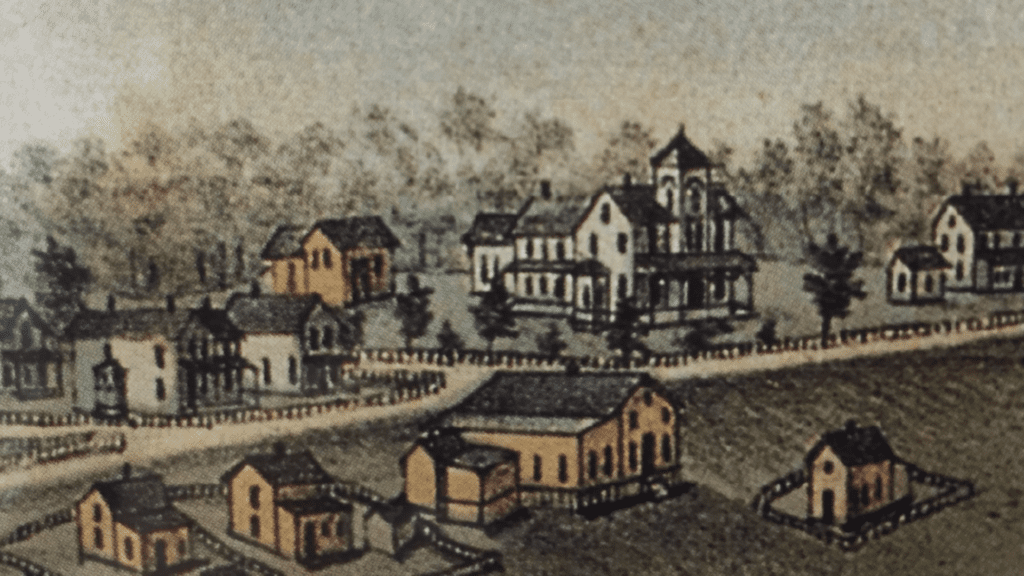

The costs associated with construction of the house appear on Quincy ledgers, “In September 1880 the Agent’s House account paid out $1,161.53 for materials and related “teaming” or freight charges. With two subsequent orders in December and January totaling $1,244.79, the majority of materials needed to build the house were in hand by early 1881 at a total cost of $2,406.32” (Scarlett, 2017). However an earlier structure is evident and shows on a map in 1865. The house was more lavish than other mine company structures and served as social center during the copper mining boom. This area boasted to be one of the wealthiest places in the USA from the late 19th-early 20th century. In 1976, this house was listed by the Michigan Historical Commission on the State Registry of Historic Sites. It has been owned by Charles S. and Angela Anderson since 1972. The 177 page Report on the Property’s History and Current Condition of the Quincy Agent’s House, completed by Dr. Sarah Fayen Scarlett in 2017 provides extensive information related to the house from archival records, modern surveys, historical contextualization and research. Dr. Scarlett summarizes the findings of the house, “This study uncovered significant information about the original construction of the house, barn, and garage, and provides historical context for their construction and use. Financial records in the Quincy Mining Company collections at MTU reveal that the company used its own carpenters and local suppliers to build the house between 1880–1882, but it also hired specialists to provide the Italianate-style finishes and other features that differentiated this large house from the company’s standard domestic buildings. The form of the house suggests both national and local design influences. The house retains significant early paint finishes, wallpaper history, utility systems, structural details, and decorative features that together offer rich possibilities for interpreting the work of carpenters and domestic servants, daily life of the local elite, social stratification, the company’s ambition, and changing fashions in the 1880s. The barn, which was built around the same time as the house, featured up-to-date systems for ventilation, feed storage, and efficient circulation of carriages, horses, and staff. The garage, built in the 1910s, suggest that the Lawtons were keeping pace with the national transition to automobiles, and that they embraced new technologies that came with them, like a fireproof garage.

of carpenters and domestic servants, daily life of the local elite, social stratification, the company’s ambition, and changing fashions in the 1880s. The barn, which was built around the same time as the house, featured up-to-date systems for ventilation, feed storage, and efficient circulation of carriages, horses, and staff. The garage, built in the 1910s, suggest that the Lawtons were keeping pace with the national transition to automobiles, and that they embraced new technologies that came with them, like a fireproof garage.

The property’s well-preserved architecture and its prominent site offer the region’s best opportunity to publicly interpret the way mining companies used domestic architecture to create and sustain the authority of their agents. Future collaboration with the National Park Service to restore the fence and other landscape features and to use the grounds, if not the house itself, for public programming could contribute significantly to the region’s heritage narrative. The Quincy Agent’s House also offers an exciting opportunity to interpret the intertwined relationship between Keweenaw geology and cultural development.” The full report, which includes the every agent and steward of the house, is available upon request.